College students spend their spring break in a number of ways: some return home to see family, while others join friends on a vacation, possibly to a mountain ski resort, or a warm beach for relaxation in the sun. Some got some extra lifting and running to get ready for spring workouts.

Get to know Kelvin Beachum, Jr., and it will come as no surprise that he spent his spring break in a completely different way.

|

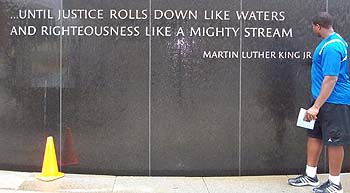

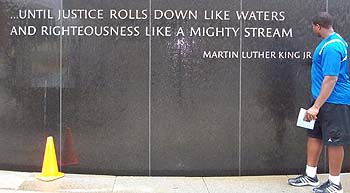

| Beachum and his classmates went to the Lorraine Hotel in Memphis, where Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated (photo by Kelvin Beachum, Jr.). |

|

While most students lug their books around in a backpack, the MustangsΓÇÖ starting left tackle totes a professional-looking briefcase.

Many students balance their schoolwork with an extracurricular activity or a part-time job. Beachum is working on his Master’s of Liberal Studies degree … and putting in the time and work that goes into being a college athlete … and he is president of SMU’s Student-Athlete Advisory Committee (SAAC) … and he is running for a position on the national SAAC … and he is on SMU president R. Gerald Turner’s Commission on Substance Abuse … and he serves on the Student Affairs Leadership Council … and is on the SMU Athletic Council … and serves on the Apple Committee (a drug awareness group for student-athletes) … and serves as student representative on SMU’s Board of Trustees … and is running to become a student trustee this year … and is a member of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes. For good measure, he serves on three committees at his church and earlier this week was named one of 10 recipients of SMU’s prestigious “M” Award, the most highly prized recognition bestowed upon students, faculty, staff and administrators on the SMU campus (given to those who are deemed to be “an inspiration to others, giving unselfishly of their time and talents in order to make the University, and indeed the world, a better place for all of us to live.”)

So while many of his friends and teammates were relaxing in the sun on a beach somewhere, the Mexia, Texas native and 36 other students took a trip through four states on which they visited a number of historical landmarks from the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

ΓÇ£Any time there is a story, thereΓÇÖs two sides,ΓÇ¥ Beachum said. ΓÇ£When you read it in a book, thatΓÇÖs one side. But when you go see these people, you get all sides. I wanted to know what it meant to be in that time.

ΓÇ£You canΓÇÖt go back and relive the Civil Rights movement, but you can talk to people who were there. I talked to a neighbor of Dr. (Martin Luther) King (Jr.), and the neighborΓÇÖs daughter, who played with (KingΓÇÖs) kids. Their time on this earth isnΓÇÖt too much longer, so you have to be able to utilize their knowledge, and what it is to be an African-American.ΓÇ¥

BeachumΓÇÖs class is taught by Dennis Simon, Altshuler Distinguished Teaching Professor in the Department of Political Science. Simon said that the impact the trip made on Beachum was a result of the investment Beachum made to understand the places the group visited and to get to know the people they met.

|

| With Minnijean Trickey, one of the Little Rock Nine (photo by Kelvin Beachum, Jr.). |

|

ΓÇ£We get to hear and interact with many veterans of the civil rights movement on this eight-day trip,ΓÇ¥ Simon said. ΓÇ£It amazed me how Kelvin developed an instant rapport with each of them. Kelvin wasn't simply learning history or politics; he was absorbing it on a one-to-one, personal level. He helped make the trip memorable for all of us and was a great ambassador for SMU.ΓÇ¥

The class visited some of the most infamous locations from the Civil Rights Movement, including:

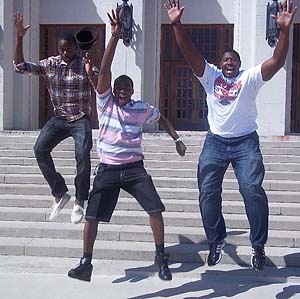

ΓÇó Central High School in Little Rock, Ark., which was integrated in 1957 with the arrival of the ΓÇ£Little Rock Nine,ΓÇ¥ the first African-American students to enroll at a previously all-white school despite the objections of the students and even Arkansas governor Orval Faubus.

ΓÇó The Jackson, Miss., home of civil rights activist Medgar Evers: ΓÇ£ItΓÇÖs a period piece museum now. You canΓÇÖt sit on the furniture, and in one room you canΓÇÖt have too many people in there at once, or it will shift,ΓÇ¥ Beachum said. ΓÇ£WhatΓÇÖs so powerful is that you can still see blood stains on the concrete from when he was shot in the back.

“That made just about all of us tear up. For one human to shoot another human in the back … but to shoot another human in his back, where his kids can see his chest blown through, and then they have to bring him inside to a mattress, then bring him out to get him to a hospital, then to be told ‘you can’t get treated here because we can’t put blood of a white man into a black man … we were where that family lived, touching the same furniture they touched. Think of a mother or a wife having to watch that. Put yourself in that situation — that’s when it really hits.”

ΓÇó Philadelphia, Miss., where three men ΓÇö James Chaney, who was black, and Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, who were white New Yorkers ΓÇö were killed by members of the Ku Klux Klan on their way back from Freedom Summer, a movement to make people aware of their voting rights.

“We went to church at the Mount Zion Methodist Church, which was burned twice by the Klan and rebuilt,” Beachum said. “I’m Pentacostal and they’re Methodist, so it was a little different, but it was a really nice service. Back at our hotel, we were greeted by Minnijean Trickey, who was one of the Little Rock Nine who helped integrate Central High School in Little Rock. She told us a lot of things, like how she would bring a change of clothes to school because she would have acid poured down the stairs on her. She’d get hit, she’d get spit on … she had a guard everywhere she went.”

ΓÇó Selma, Ala., the site of ΓÇ£Bloody Sunday,ΓÇ¥ where marchers went over the Edmund Pettus Bridge; when they got across the bridge, they were greeted by Selma police and Alabama state troopers and beaten back across the bridge.

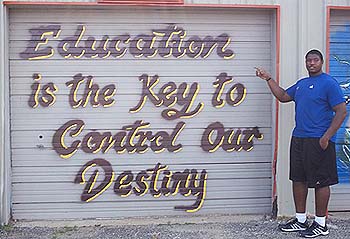

|

| Beachum is in graduate school, having earned his undergraduate degree in economics with a minor in sports management (photo by Kelvin Beachum, Jr.). |

|

ΓÇ£Our tour guide in Selma was Joanna Bland ΓÇö she was 8 years old when that happened,ΓÇ¥ Beachum said. ΓÇ£She got knocked unconscious, and her sister was beaten up.ΓÇ¥ The Bloody Sunday march over the bridge was a dual-purpose event: for voting rights, and to protest the murder of Jimmy Lee Jackson.

ΓÇó Montgomery, Ala.: ΓÇ£We visited the Rosa Parks Museum and the church where Dr. King pastured for a couple of years leading up to the Civil Rights Movement,ΓÇ¥ Beachum said. ΓÇ£We also went to a memorial there for Dr. King, and saw the dates and names of people who were killed. ThereΓÇÖs water flowing over these memorials to symbolize that what they talked about and what they taught would never be forgotten.ΓÇ¥

ΓÇó Oxford, Miss.: ΓÇ£James Meredith was the first African-American student at Ole Miss. We saw (SMU) President (R. Gerald) TurnerΓÇÖs picture on wall coming out of library at Ole Miss ΓÇö he looked young.

ΓÇ£Being on that campus, I walked around alone. I pictured what it would have been like if I were there at that time, 40 years ago. I donΓÇÖt know that I could have reacted non-violently to what they went though. It would have been hard, during that whole movement, not to do anything violent ΓÇö it would have been kind of rough.ΓÇ¥

• Memphis, Tenn.: “We went to the Lorraine Hotel, where Dr. King was assassinated. It was really powerful, seeing the bloodstains on that cement. Walking through the rooms he came out of … they really try to keep those period pieces as they were at that time. On the other side of the street, they have where the gunman was. We read about the conspiracy theories.

ΓÇ£We also went to the Stax Museum, where they say soul music originated in the South ΓÇö that was a sight to see ΓÇö and I went to Beale Street. I never went to a club in my life before that, but I went to the Juke Joint and to B.B. KingΓÇÖs blues club and the Pepsi-Cola Pavilion, where they have ΓÇÿlow-down dirty blues.ΓÇÖΓÇ¥

PERPETUAL STUDENTFor Beachum, who already received his economics degree with a minor in sports management, the trip he took was more than merely a requirement for his class or a chance to visit places he had never visited.

ΓÇ£I always wanted to know about what my people went through, the African-American race,ΓÇ¥ he said. ΓÇ£ItΓÇÖs kind of ironic ΓÇö IΓÇÖd call home and say ΓÇÿdo you remember this? Why didnΓÇÖt you teach us this?ΓÇÖ

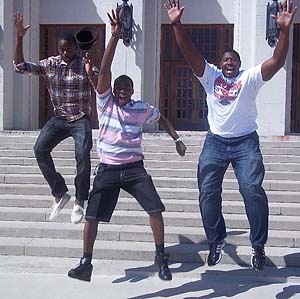

|

| Beachum and classmates jumping off the steps at Central High School in Little Rock, Ark (photo by Kelvin Beachum, Jr.). |

|

ΓÇ£My mom and dad did teach us ΓÇö they taught us (Beachum has one brother, Jacob, along with two sisters, Krystal and Brechelle) to be African-American men, to be men of integrity.ΓÇ¥

Beachum sounded encouraged about how far society has come toward desegregation, but said it is not yet a thing of the past.

ΓÇ£The fight is not over ΓÇö it has taken some twists, but itΓÇÖs not over,ΓÇ¥ he said. ΓÇ£ItΓÇÖs not as bad as it was, but itΓÇÖs still going on today.

The racial imbalance, Beachum said, is felt close to home, and he would like the chance to improve it.

ΓÇ£IΓÇÖve made a statement, that before I die, IΓÇÖm going to be mayor of Mexia, and I want to be governor of Texas. Those are lofty goals, I know, but I know enough people who can get me in some doors.

ΓÇ£Doing whatΓÇÖs required is never enough. You have to find a way to add a little extra, too.ΓÇ¥

Beachum said he expects the pilgrimage his class made has had an impact on him that will last, and extends beyond the way he thinks about race relations.

ΓÇ£I really think it changed me. It makes me want to work even harder than I do, to do more ΓÇö always do more, on the field or taking guys under my wing,ΓÇ¥ he said. ΓÇ£ThereΓÇÖs more to football than football. I say that, and people say, ΓÇ£you donΓÇÖt care a lot about football.ΓÇ¥ Not true ΓÇö I care a lot. You look at guys like Peyton Manning, Ray Lewis ΓÇö they have good character, and they work on their image.

ΓÇ£Perception is reality ΓÇö thatΓÇÖs why I walk around with a briefcase. IΓÇÖm going to be in that world one day. You want to go to league? Working for the league starts the day you walk through the door. If youΓÇÖre perceived to be (that guy) who doesnΓÇÖt work at all, thatΓÇÖs who you are. You canΓÇÖt get there if people donΓÇÖt think youΓÇÖre willing to put in the work.ΓÇ¥

Beachum has identified a handful of young players who he has taken under his wing, taking on a mentor role so he can share what he has learned … not just on the trip he took with his class, but since his arrival at SMU, in a year that almost convinced him to leave.

ΓÇ£My first year (in 2007), I redshirted and we went 1-11,ΓÇ¥ Beachum said. ΓÇ£I didnΓÇÖt want to be here. But when Coach (June) Jones first met me, he said, ΓÇÿyouΓÇÖre going to be NFL.ΓÇÖ HeΓÇÖs a visionary, he knows how to speak into your life. Whether you take his words and use it, thatΓÇÖs up to you. I took those words and tried to live up to it, not only for him, but for me, too. For him, having done that, he had a huge impact on me.

ΓÇ£Coach Jones has put that shot of confidence and put that belief in me, that respect. God placed a man named June Jones in my life, a man who said some really powerful words to me. I give thanks first to God, then my family, and then Coach Jones and (former special teams) Coach (Frank) Gansz before he passed away, (offensive line) Coach (Adrian) Klemm ΓÇö they have been at side from day one.

ΓÇ£The people around you ΓÇö your family, the people you work with ΓÇö they all contribute to who you are. Those people we met on the trip, theyΓÇÖre part of all of us.ΓÇ¥